Justice for the Victims

When it became clear at the end of 1978 that the excesses and arbitrariness of the Cultural Revolution had come to an end once for all, many victims of political persecution under Mao nourished new hope for rehabiltation.

The circumstances how and when citizens had suffered from repression seemed quite diverse: The mass campaigns of the early 1950s targeted "capitalists", "landlords" or "Kuomintang spies" (and various other "black categories"), in the 1960s it were mainly "rightists" and critics from within the party hierarchy, sometimes even high-ranking politicians.

At last it were the numberless victims of the Cultural Revolution, the "black categories" again, but now also many intellectuals, teachers and cultural workers, or just simple citizens who have been denounced by neighbors or coworkers. During the first months of the "Cultural Revolution" many have been just slain by Red Guards, others were condemned in show trials, quickly executed or sent to prisons and labor camps. Cadres and intellectuals were - with varying justifications - sent for "re-education" and "manual labor" to remote rural areas, sometimes with their families, which meant that they permanently lost the right to reside in the cities. Others again were just put under house arrest ("under the supervision of the masses") by "revolutionary committees" of their work place, a special form of restrictions and harassment.

Political Repression and Personal Grievances

When millions of victims of political campaigns demanded rehabilitation and compensation at the end of the 1970s, they advanced their claims in different ways: Many wrote letters or petitions to the government, but some brought their complaints to the public, describing their cases on big-character posters. Tens of thousands traveled to Beijing or a provincial capital to personally contact authorities. In Beijing thousands camped under the open sky around the offices of the Public Security Bureau near the south eastern corner of Tiananmen Square.

The Central Government and local authorities established special offices and commissions to deal with the petitions and claims for rehabilitation of political victims. Many asked for the revocation of court decisions, of negative political classifications that were still contained in personal records (for example as "counter-revolutionaries" or "class enemies"), or they demanded a return to their previous workplaces. Those deported to remote rural areas wanted to go back to the cities, others claimed confiscated belongings or wanted to return to their former apartments that had been taken away from them.

But there are not only victims of "political" persecution who raise their voices, many individuals who feel harassment or discrimination at their workplace or in their personal environment, also publicly express their annoyances, as they find it difficult to address somebody with their grievances in the rigid and hierarchical system. Sometimes even personal quarrels are reflected in big-character posters.

The First Spontaneous Demonstration

When on November 25 several hundred democracy activists and petioners debated in front of the newly inaugurated "Democracy Wall", a big variety of topics were touched upon: The rising food prices just as the Mao anthem "The East is Red" that promises nothing less than a "savior".

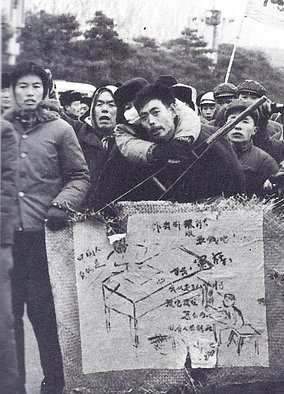

One of the speakers demands a separation of powers between government, legislature and judiciary, another one strongly criticizes the Cultural Revolution. The unthinkable happens on November 27, it is probably the first spontaeous protest march against the government and Communist Party policies ever since 1949. About ten thousend demonstrators brave the cold on their way to Tiananmen Square, passing "Xinhua Men" (新华门), the "Gate of the New China", which is the entry to the seat of the government and the CCP Central Committee.

"Down with hunger, down with repression, we want human rights, we want democracy" is written on one of the hastily produced banners. The terms "democracy" and "human rights" are by themselves an outright provocation at that time. (A TV report for ABC by Jim Laurie shows - after about 2'20 minutes - short scenes from this demonstration.)

Fu Yuehua (傅月华)

The key figure in Beijing at that time who supports the petitioners (上访者 in Chinese) and tries to co-ordinate their actions is the 31 years old woman Fu Yuehua. She sees herself as a victim of a yearlong harassment by officials, a superior she says, abused this dependency relationship to sexually assault her several times. Her numerous complaints to the authorities only have the consequence that she receives threats, gets slandered and finally loses her job.

In 1978 after the first demonstration, she joins the numerous petitioners who are gathered in central Beijing, she writes posters and organizes a "Committee of Petitioning Citizens" that prepares another protest march for January 8, the anniversary of Zhou Enlai's death. This rally voices again harsh criticism of the government and the party. The authorities are baffled at first, but ten days later they decide to react. On January 18, Fu gets arrested, almost a year later she is tried and condemned to two years in prison for "disturbance of public order" and "libelling" (because she had accused her superior of rape).

Shortly after her arrest, activists of the Democracy Movement publicly speak out for Fu Yuehua. They send delegations to the police department and to the prison where she is held, and her case becomes a central topic for the new independent journals: "Explorations" and the "April 5th Forum" as well as "Human Rights in China" support Fu Yuehua, they demand explanations and her immediate release, and say that her case would be a yardstick for the freedoms of expression and demonstration guaranteed by the constitution.

Despite the arrest of Fu Yuehua, authorities continue to deal with the injustices of the past. More than three million victims of the Cultural Revolution, and another half a million who were persecuted during other political campaigns of the 1950s and 1960s, have been, according to official figures, rehabilitated during the years after Mao's death, probably many more at local levels and counting also those who have not gone through formal procedures, but benefitted from collective compensation measures.

One may note that high-ranking officials often were rather quickly rehabilitated by political decisions while common citizens had to take initiative themselves. Proceedings were often slow, but many victims were impatient to get rehabilitated after years of repression.

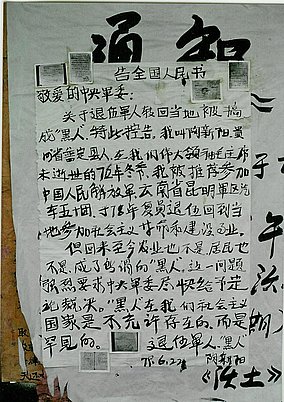

Poster Written by One of the Petitioners at the Beijing Democracy Wall

"Letter to the entire people of China.

Dear Central Military Commission:

We are talking here about a demobilized soldier that has been made a 'black element'. His name is Tao Xinyang, he comes from Puding County, Guizhou Province. In summer 1976, when our Great Leader Chairman Mao was still alive, I was endorsed to join the People's Liberation Army and attached to the 50th motorized unit of the Kunming Military District, Yunnan Province. After my demobilization in 1978 I went home to participate in the socialist revolution and construction.

But after my return I neither belonged to rural agriculture nor to the city residents, I became a so-called 'black element', which should not even exist in our socialist society, and which also is a rare appearance. A demobilized soldier an 'black element'. Tao Xinyang. 22. 6. 79" (with several photos of the correspondence attached)