Hu Yaobang and the Democracy Movement

The big changes towards a reform policy, and the beginnings of the Democracy Movement and the dazibaos at the Xidan Wall, all coincide with the rise of the former Youth League official to the inner circle of the Chinese leadership.

Hu Yaobang served as Secretary General of the official youth organization between 1952 and 1966, before he was purged during the Cultural Revolution. He was publicly humiliated and eventually sent to a camp for "re-education through labor". His fate became closely linked then to that of Deng Xiaoping who had also been persecuted. When Deng was temporarily allowed back into politics between 1973 and 1976, Hu was also permitted to become active again, but in April 1976 he was deposed once more together with Deng Xiaoping, and only in 1977, when Mao had died, he was eventually rehabilitated - just as Deng Xiaoping.

Among other tasks, Hu became responsible in the party for the rehabilitation of Cultural Revolution victims, later he was head of the powerful Propaganda Department of the CCP Central Committee, in 1980 he was chosen for a seat in the Politburo Standing Committee (the highest party organ), and he became Secretary General of the Communist Party. The next year he was formally made its Chairman to follow Mao's originally chosen successor Hua Guofeng. But the real political power shifted more and more into the hands of Deng Xiaoping, although Deng had renounced to hold any formal top positions.

Hu and others from his reformist faction supported in various ways the new grassroot Democracy Movement and the right to publish critical posters. And they opposed or criticized the arrest of well-known dissident Wei Jingsheng. They viewed the dissidents as allies in their struggle against the old Maoist cadres who still occupied many key positions in the political hierarchy. At least between the end of 1978 and March 1979, there seemed to exist a possibility that the ideas of the "Beijing Spring" might take roots and embrace larger parts of the Communist Party to become the foundation of a Chinese reform communism. One reason that this has not happend, was Deng's political turnaround. The titular Party Chairman Hu Yaobang eventually had to give in to the authority of the de facto leader Deng Xiaoping.

Memories of an Exiled People's Daily Editor

Hu Jiwei who was chief editor of the main party newspaper People's Daily at that time, published in 2004, when he was already in exile in the US, some memories under the headline "Hu Yaobang and the Xidan Democracy Wall" (English translation thanks to Australian sinologist Andrew Chubb, minor corrections and notes by Helmut Opletal) where he tells how the party leader sympathized with the dissident movement, and how he came himself under attack for this. Hu Jiwei explains :

When the Democracy Wall first appeared, the central leaders all followed it very closely. Chen Yun issued special instructions for the People's Daily to send a reporter deep into the midst of the crowd to relay the movement's dynamics and situation. The paper dispatched Internal Political Bureau editor Wang Yong'an to perform this task. I repeatedly warned him to do no more than try to learn the situation, understand its direction and ask for materials, and to absolutely avoid declaring his own opinions. Wang Yong'an wrote numerous 'internal' reports for the central leadership.

I sent many reports about the Xidan Wall to Yaobang, and attended a small meeting he chaired.

In short, Comrade Yaobang was greatly interested in the Xidan Democracy Wall, having already indicated his admiration for it, and believed its big-character posters to be different from those of the Cultural Revolution and before. He believed that in the past they had mostly been used by leaders to punish and harm people. This time, the big-character posters were like those of the [1976] April 5th Tiananmen Movement, voices coming from people's hearts, a new people's awakening.

I related to Yaobang how people were rushing to Beijing to petition, how some were taking to the streets with their complaints, others writing big-character posters, and still more sitting outside government offices silently asking for their petitions to be heard. I told him how this had greatly shocked some leaders in power, who had called loudly for order to be restored at once. I said this was a positive effect of his political rehabilitation programme. Most of the severely wronged cadres and ordinary people had seen how the central government was now encouraging rehabilitations, and many were now rushing to county and provincial capitals, showing their trust in and dependence on the central government and their belief that, with the central government now doing what was right, there was hope that their problems could be solved.

Yaobang agreed. He said that the rehabilitations had only just begun, so all over the country much work had to be done on the incoming letters and petitions, and every effort made to solve local problems locally if possible, in order to avoid involving the central government. While Yaobang continuously enlarged the scope of the rehabilitations, he also sent instructions to Party, government and news organisations everywhere to work harder on incoming letters and petitions. ...

Comrade Yaobang also saw the petitioners' hanging of big-character posters, the formation of people's organisations and the emergence of people's publications as greatly important, and directed all news organisations to be sure to reflect this situation in their reports. The People's Daily published at that time special editions of the "Situation Summary" [Qingkuang Huibian 情况汇编] for the central government that included a selection of Xidan Wall big-character posters and excerpts from some longer posters and articles from the people's publications. We also published an 'F.Y.I.' loose-leaf anthology for a small number of leaders. Other newspapers, periodicals and related work units in Beijing also specially published this type of internal reference material during this period.

For a period of time, the Guizhou people's organisation called the "Enlightenment Society" was very active in Beijing. In order to understand the Enlightenment Society's circumstances, Yaobang got the People's Daily to send a reporter to investigate. The office sent commentator Comrade Zhou Xiuqiang to Guiyang. After Zhou returned from his investigation, Yaobang summoned him specially to his office to hear his findings. ... (Hu Jiwei: Hu Yaobang and the Xidan Democracy Wall)

It has been known from other sources as well (such as the memories of party historian Li Honglin) that Hu Yaobang opposed Wei Jingsheng's arrest in March 1979, but that he eventually had to give in to Deng Xiaoping's orders. Hu Jiwei:

After the arrest of Wei Jingsheng at the end of March 1979, Comrade Yaobang indicated his disagreement in a speech to the Second Session of the Fifth National People's Congress in June. Yaobang said: "I support anyone exercising their democratic rights under a socialist system. I hope everyone can enjoy the greatest freedom under the protection of the Constitution. Despite the numerous comrades criticising me by name or otherwise during the Central Work Conference and this People's Congress, saying I was going behind the central government's back, supporting a so-called democratisation movement that violated the Four Modernisations, and encouraging anarchy, despite all that I still maintain my views." Regarding Wei's arrest he said: "I respectfully suggest that comrades do not arrest people who engage in struggle, still less those who merely show concern. Those who are brave enough to raise these problems, I fear, will not be put off by being thrown in jail. Wei Jingsheng has been held for more than three months, and if he dies he will become a martyr of the masses, a martyr in the hearts of all." (Hu Jiwei: Hu Yaobang and the Xidan Democracy Wall)

Hu Yaobang apparently also initiated articles in the big party media to support the rights of free speech and debate. On November 14, 1979 (just a few weeks after the harsh verdict of 15 years in jail against Wei Jingsheng), the People's Daily carried an article advocating that one should be able to speak out without being threatened by punishment. But Politburo member Hu Qiaomu complained to Deng Xiaoping that the People's Daily were supporting Wei Jingsheng by downplaying his "crimes". But this article had been edited and authorized personally by Hu Yaobang, says Hu Jiwei.

Hu Yaobang's Continued Support for Big-Character Posters

A People's Congress session in November 1979 and the following session in September 1980, eventually passed several measures that implied a closing down of the Democracy Wall, such as the removal of "Four Big (Freedoms)" (that included the right to write big-character posters) from the Chinese constitution. Hu Jiwei reports that Hu Yaobang had originally supported the idea to establish a "Democracy Park" in the Workers' Cultural Palace in the center of Beijing, but eventually agreed to move the Democracy Wall to the more distant Yuetan Park. Nevertheless, despite the abolishment of the Four Big (Freedoms), Hu Yaobang wanted to retain some possibilities to publish big-character posters:

Thus, I suggest that if a poster is signed and taken responsibility for, presents the facts and talks reasonably, it should be allowed to be posted within the author's work unit. This is completely different to the Four Bigs, representing instead the right to free speech that the people should have and that no person can deprive them of. The rules of the Four Bigs and Big Democracy have been deleted from the Constitution but that absolutely does not mean that all hanging of big-character posters now violates the Constitution." My view was that only the indiscriminate hanging of big-character posters on the street should be prohibited, and that they should always be allowed in appropriate places within the grounds of government departments. Our newspaper should run more mass opinions, I said, and our publishing unit's internal publications had to run more letters, petitions and complaints in order to provide more opportunities for the masses to express their opinions. I discussed these opinions with Yaobang and he agreed with all of them. (Hu Jiwei: Hu Yaobang and the Xidan Democracy Wall)

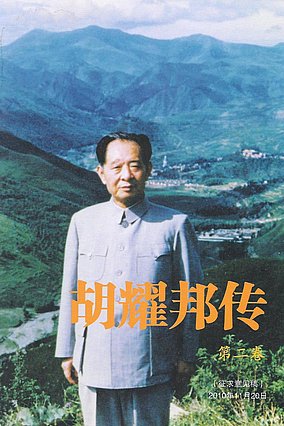

The Controversial Biography of Hu Yaobang

The biography of Hu Yaobang published in 2010 in an internal printing at first ("Copy for Collecting Opinions", Nov. 20, 2010, giving neither a location nor an editor), carries a number of quotations that confirm Hu Jiwei's memories and portray the former Chairman and Secretary General of the CCP as a sympathizer of the Democracy Movement and the dazibaos. Hu Yaobang's views are described like this:

Hu Yaobang has repeatedly made remarks on the events and opinions that had come from the masses and especially the youth on the development of democracy: He said that the people at the Xidan Democracy Wall and other places had thoroughly exposed the crimes of Lin Biao and the counter-revolutionary Jiang Qing Clique and their "leftist" machinations, and strongly demanded rectifications. They had stopped those "leftist" schemes, and in a spirit of creativity, brought many ideas and suggestions into the political life, changing the general mood in our party and our socialist society from a pessimistic one to one full of hope. All those who made complaints, drafted petitions or asked for rehabilitation of people who had suffered from arbitrary injustice, were also expressing hope and trust into our party and government. When some individuals, through posters and privately published journals, expressed views and made suggestions in order to change a situation where only one opinion was allowed, then this were also a phenomenon that galvanized the people and livened the country up. ... In early February, during the Forum on Theory Work [January-March 1979], ... he said on the demonstrations, rail blockades and attacks on government buildings in Shanghai: We should just do our work thoroughly during two or three months, then these tiny disturbances were certainly eliminated. And he asked propaganda units like the People's Daily to spread a positive mood and guidance; he suggested that institutions concerned should send officials to the independent groups to patiently convince them to leave their wrong path. (Hu Yaobang Zhuan, pp. 139-140)

The Beginning of Hu's Failure

The biography of Hu Yaobang only touches briefly upon the events of the "Beijing Spring". But it confirms Hu Jiwei's memories by giving some more examples how Hu Yaobang expressed his sympathies, though without giving too much insight under which circumstances he eventually changed his mind (or gave in to Deng Xiaoping's authority).

Hu Jiwei quotes from another article that he says has been edited by Hu Yaobang. It appeared on December 21, 1978 over several pages under the headline "Long Live the People", and seemed to support the Democracy Movement that had just started and its critical posters:

Yaobang coordinated the writing of it under the name 'Special Commentator'. ... This article came out just as the Xidan Democracy Wall mass movement was flourishing, so when it sang the praises of the April Fifth Tiananmen mass movement [of 1976] it was essentially praising the Xidan Democracy Movement too. ... The time chosen for the article's publication was just as the Xidan Democracy Wall was peaking and creating fear among some of those in power. This showed Hu Yaobang's thorough open-mindedness towards the new-era democratic movement. ... Soon after the end of the Cultural Revolution, as people were savouring that triumph, Comrade Yaobang reminded the Chinese people to celebrate on the one hand the emergence of new forces for people's democracy, but on the other to be more alert in order to avoid complications. As time has passed, the historic masterpiece that he oversaw the writing of more than twenty years ago has appeared increasingly brilliant.

Yaobang initiated the political rehabilitations when he had only just returned to the political stage. ... There were people who asked bluntly: "Will the Gang of Four stage a comeback?" I remember that at the time Yaobang answered clearly: "The Gang cannot come back, but it is possible they will be reincarnated in someone else's body."

This shows Yaobang's foresight. However, later facts showed that Yaobang also had significant limitations, for during the Theoretical Work Conference in early 1979 some particularly forward-thinking comrades raised the issue of Mao Zedong's criminal responsibility for the Cultural Revolution and whether we should be talking about a Gang of Four or a Gang of Five. Unfortunately people of this type were few in number; the majority of the Party elite had not arrived at that level of awakening. I myself also had not. (Hu Jiwei: Hu Yaobang and the Xidan Democracy Wall)

From these brief remarks, one can see that Hu Yaobang's opinions differed from the party mainstream already at an early stage, eventually giving up his efforts trying to change the party line:

As far as I know, Hu Yaobang knew all about the shifting circumstances that surrounded the arrest of Wei Jingsheng and the banning of Democracy Wall. He was clear on Deng Xiaoping's "Uphold the Four Cardinal Principals" and the gradual backsliding of the central Party's anti-leftist policy. He knew about Hu Qiaomu's deletion of the vital section of Commander Ye [Jianying]'s speech to the Third Plenum – "The Third Plenum is a model of internal Party democracy; the Xidan Democracy Wall is a model of people's democracy" – from the official record. Afterwards Hu worked at developing and consolidating the two democratic forces and bringing them closer together towards the creation of a new democratic wave. Just think: if the spirit of the Third Plenum – the "model of internal Party democracy" – had been successfully implemented, and the "model of people's democracy", Xidan Democracy Wall, had been able to develop smoothly, if the two had really come together, what would our country's new democracy movement have become? It is worth pondering. As it happened, Yaobang rallied ... central leader-comrades to devote their all to implementing a guiding policy centered on economic construction. ... Step by step, they corrected layer upon layer of errors from the era when Mao was in charge. It seems that as this great reform movement proceeded, spurring the rapid development of the entire national economy, Yaobang was increasingly powerless to halt the Party's retreat from the anti-leftist policy following the Four Cardinal Principles speech [by Deng Xiaoping]. (Hu Jiwei: Hu Yaobang and the Xidan Democracy Wall)

Hu Yaobang could never put into practice his obvious conviction that economic development had to be accompanied also by thorough political reforms. But Deng Xiaoping's growing political power (and Deng's differing views on the issues of freedoms and democracy) accelerated Hu's failure. In 1987 he had to relinquish his post of Party Secretary General. He was accused of laxness and supporting "bourgeois liberalization", and of his refusal to purge three reform-orientated officials and intellectuals from the party as Deng Xiaoping had asked him to do. Two years later the reformer and innovator died from a heart attack. When students started an unauthorized public mourning after his decease in April 1989, this became the beginning of the Tiananmen protests, of a new democracy movement that was eventually put down by military force on June 4th, 1989.