The Chinese Democracy Movement 1978-1981

Beginnings and Expansion of the Democracy Movement

When in November and December 1978 initial details about a reform conference of the CCP Central Committee ("Third Plenum") and planned economic changes leaked out to the general public, this immediately created an euphoric mood all over the country. Already before this conference some local authorities had started to distribute agricultural land of the former "People's Communes" to individual peasants and allow them to grow and market a large part of their production at their own discretion and responsibility. Many officials, intellectuals and grass-root citizens also hoped for political changes in fields that had been severely harmed by radical policies under Mao: culture, media, education, national minorities and religious institutions, freedoms in daily life.

People who had been persecuted during the Mao era demanded rehabilitation and compensation from the authorities in Beijing, and such victims of the past were among the first now to raise demands for human rights and political democracy.

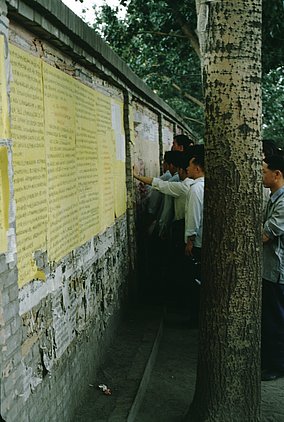

These so-called "petitioners" (上访者) started to express their demands in big-character posters (dazibao) which they glued to walls and buildings in central Beijing in order to reach a wider public. Besides many individual complaints and accusations, there also appeared more general political declarations that went far beyond the personal complaints of the "petitioners".

Within short time a few places in the center of Beijing emerged as the preferred locations for such written protest: the external walls of the former Imperial Palace, part of which now served as the seat of the government and the party leadership; the shopping street Wangfujing (王府井), where the offices of the party newspaper "People's Daily" (Renmin Ribao 人民日报) were located, and the several hundred meter long brick wall of a municipal bus terminal at the crowded Xidan intersection in the western center of Beijing.

It was this place that people soon started to call "Democracy Wall" as it also became a meeting place for activists to debate and to distribute and sell the new independent journals produced by simple means, "people's papers" as they started to call them.

Center and Periphery

In several dozen other cities - Shanghai, Qingdao, Tianjin, Guangzhou, Wuhan - people soon followed the example of Beijing, publishing independent journals and creating their own Democracy Walls where dazibao were published and political developments debated. One of the first groups who traveled to Beijing to join the emerging movement were four young artists from the south-western Guizhou province. They called themselves "Enlightenment Society" (Qimeng She 启蒙社), and already at the end of 1978 they published their political manifesto in Beijing.

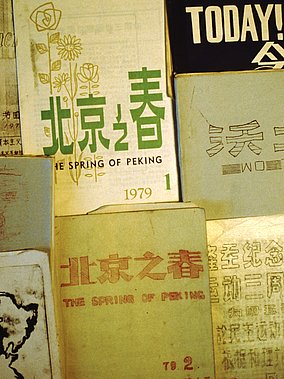

Many dazibao and most of the new magazines focussed on political freedoms and "democratization" although those ideas often remained sketchy and superficial at that time. But already in early 1979 the term "Democracy Movement" was used, and activists talked about a "Beijing Spring", deliberately referring to the Czechoslovak communist reform movement of 1968, the so-called "Prague Spring".

One of the new journals also chose to carry the name "Beijing zhi chun" (北京之春), adding on its cover the English title "The Spring of Peking". Many of the Chinese activists knew about the "dissidents" and the civil rights movements in Eastern Europe, about Lech Walesa and his "Solidarnosc" labour union. The communist reformers in Hungary and the (often idealized) Yugoslav model of socialism based on "workers' self-management" have equally inspired the Chinese democracy activists.

Short-lived Pluralism

During the following months independent journals and the Democracy Wall saw ups and downs. The leaders in Beijing seem undecided how to deal with the new popular movement. Many activities are at first tolerated, others are quickly forbidden. A few activists already get arrested during the initial weeks, but many others remain undisturbed.

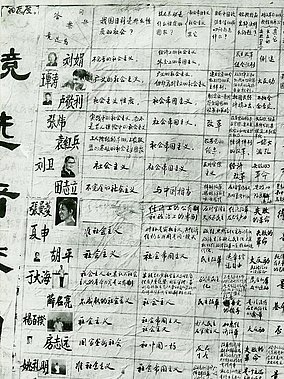

But in November 1980 the Democracy Movement comes to an unexpected revival, when in accordance with a new electoral law, citizens are allowed to directly vote for deputies to local "People's Congresses" by chosing between several competing candidates. Especially at some colleges and universities including Peking University, outright electoral campaigns are starting to unfold, focussing once again on the topics of the Democracy Movement such as citizens' rights, political pluralism and the role of revolutionary leader Mao Zedong. At Peking University the young civil rights activist Hu Ping wins a seat in the assembly of Haidian city district.

Artists and Writers

Many creative artists sympathized with the Democracy Movement and some published their own independent journals. The most influential of these magazines was certainly "Today" (Jintian 今天,its first issue still carried the English title "The Moment") with a number of contributing writers and artist that should later gain international fame.

About thirty avant-garde artists partcipated in the "Stars Group" (Xingxing 星星画会) that became known through their struggle for an independent art exhibition. When an open air show of their works was closed down by police, and access to official galleries denied in autumn 1979, they staged a public street protest, marching together with the political activists from the Democracy Wall. Eventually they obtained the right to organize their own exhibition.

The works of the group were rather diverse, but all of them showed a rejection of Socialist Realism and the strict Maoist approach to visual arts. Some works by the sculptor Wang Keping could be seen as outright political provocation.